April 20, 2017 – May 20, 2017

—

Curated by Jaclyn Quaresma

—

Works by Andrea Chung, Shelley Niro,

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson & Alize Zorlutuna

Additional materials by and about Doris McCarthy, Ana Mendieta, Nicholas Poussin, Elizabeth Simcoe and a reproduction of the prehistoric La Cueva de El Castillo

—

Doris McCarthy Gallery, University of Toronto Scarborough. Visit site here.

—

Visit the interactive site archive with essay and glossary here.

they’d forgotten entirely that story and reality are one and the same.

-Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, gezhizhwazh

In gezhizhwazh, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson reminds us that stories impact reality. She shows us that to make, preserve, and share stories can be an act of agency and self-determination; that to tell one’s story can be a political act and that the means and ease by which it can be accessed is of political significance.

What happens when we rearrange the current story of art history in favour of one that is rhizomatic, multi-generational, and feminist, one that accounts for local history as well as its place in the international conversation? This exhibition grounds the narrative of art in the El Castillo cave where the artwork on the walls has been attributed not only to men (as suggested by Western art history) but, in large part, to women and children. When we re-examine art (hi)story through this lens, what is possible? This question is the focus of the exhibition for there are many stories here, which engages in a conversation that spans some 40,800 years between contemporary, historic, and prehistoric artists and writers.

In the exhibition, Andrea Chung, Doris McCarthy, Ana Mendieta, Shelley Niro, Elizabeth Simcoe, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Alize Zorlutuna explore and share their (hi)stories. Their stories take the form of archive ephemera, books and diaries, soundscape and video, and pursue self-determination as a form of resistance and remembrance.

Images of the cave and the bluffs bracket the for there are many stories here. This imagery offers two distinct ways of thinking with the land and through the stories it holds. The cave, an early place of ritual, provides a model of care, preservation and protection. The cave nods to emergence, the origin of human consciousness, knowledge and truth as well as the safekeeping of tradition, whereas the bluffs present something altogether different. Bluffs, constant in their erosion, are continually releasing the past. As the grains and detritus of the rock wall leave its surface, they recalibrate amongst the waves, coming together to make a new landmass. This formation can take tens and hundreds of years but eventually the bits of old come together to make something new. Within this framework, for there are many stories here considers small acts of resistance and the stories that carry through them.

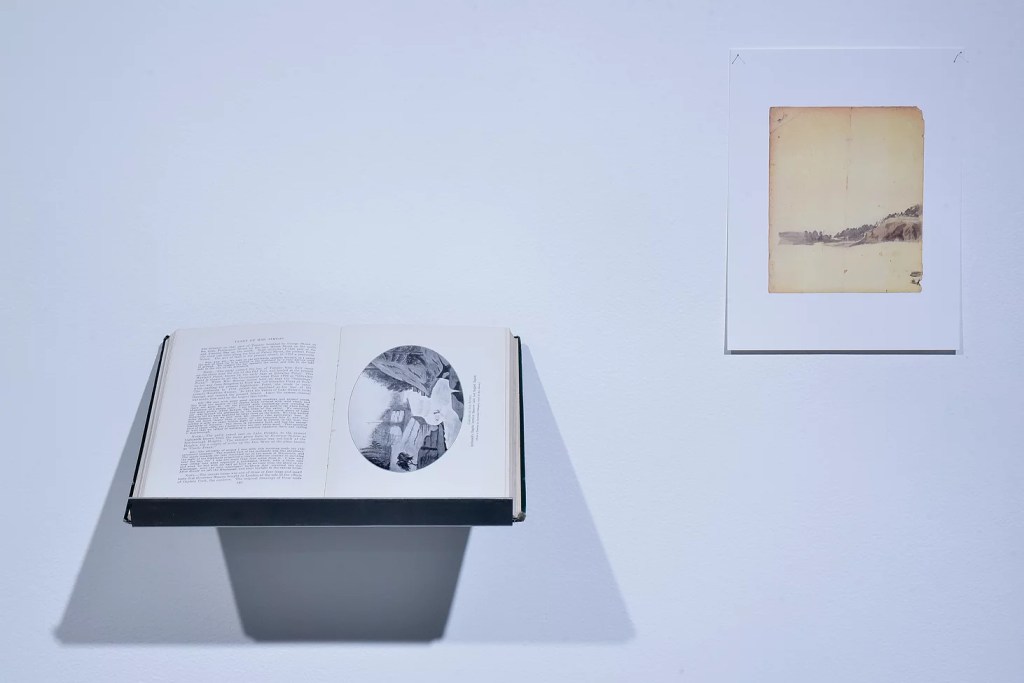

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s book “Islands of Decolonial Love” (2013) is held open to the story gezhizhwazh. As an aunty is telling the tale to a young man, the narrative addresses the complexities of telling, sharing, and revisiting stories.

Gezhizhwazh is a character sometimes featured in Wiindigo stories. Translated into English, her name means ‘to try to cut.’ [1] She is a decolonising force. In these stories, the greedy, cannibalistic beast, Wiindigo, is defeated by gezhizhwazh when she sacrifices herself to it in order keep tabs on it. Once she knew of its plan, gezhizhwazh warned the Anishinaabe people and told them how to kill Wiindigo. [2]

For Simpson, this story provides a model for Indigenous resistance, one based on strategic thinking. The method of storytelling also a resistance act because Simpsons herself is selective in her use of translation. In her version of gezhizhwazh, Simpson speaks to the tension between colonial, patriarchal language and one’s way of speaking. the intergenerational sharing of knowledge and reproduction of that knowledge. She foregrounds the possibility of change and the ability to start at the beginning— even when one is in the middle. With this in mind, this exhibition explores the question, “when we re-examine art hi(story) through a rhizomatic, multi-generational, and feminist lens, what is possible?” from the current position of the gallery.

The Doris McCarthy Gallery (DMG) at the University of Toronto, Scarborough is home to the fonds of the famed Canadian painter and writer Doris McCarthy. Of this ephemera are boxes upon boxes of her calendars and diaries from childhood onwards, documenting her daily errands, meetings, thoughts, and ideas. Though primarily a painter and less known for her writing, Doris McCarthy also wrote, not one, but three memoirs. However, it is the archived material, not her creative works that are the focus of our interest. In this exhibition, her avid self-historicizing is interpreted as a method of resistance against time and the potential of being forgotten. These chapters of her carefully catalogued life have been moved from their storage vault and into the gallery proper. At once the effort of collecting, maintaining, preserving and storing on both the part of Doris and the Gallery become evident.

Ten kilometres from the DMG, on the Scarborough Bluffs, is where one can find McCarthy’s home, Fool’s Paradise. Fool’s Paradise, too, was donated to the Ontario Heritage Trust and is kept as an artist residency. By giving her home and collection to the University of Toronto Scarborough and Ontario Heritage Trust, McCarthy determined what could be remembered about her, how it could be discovered and where it could be accessed.

Doris was extremely fond of the bluffs and was active in their preservation, often taking photographs documenting its erosion patterns and effects. Elizabeth Simcoe, the wife of Canada’s first Lieutenant General, Governor John Graves Simcoe, gave these very bluffs the name they have today. Elizabeth kept a diary in which she details her time in Canada, including the founding of colonial towns. Her perspective as a European woman differs from the accounts of her husband and historians. In one entry we find an encounter with the landscape that is now known as the Scarborough Bluffs:

4th— We met with some good natural meadows and several ponds. The trees are mostly of the poplar kind, covered with wild vines, and there are some fir. On the ground were everlasting peas creeping in abundance, of a purple color. I am told they are good to ear when boiled, our ride beyond the peninsula on the sands of the north shore of Lake Ontario till we were impeded large trees on the beach. We then walked some distance till we met with Mr. Grants (the surveyor’s) boat. It was not much larger than a canoe, but we ventured into it, and after rowing a mile we came within sight of what is named, in the map, the highlands of Toronto. The shore is extremely bold, and has the appearance of chalk cliffs, but I believe they are only white sand. They appeared so well that we talked of building a summer residence there and calling it Scarborough.

The colonial gesture of renaming a place in memory of the coloniser’s home is made visible in the gallery and speaks to the stories held and withheld by a name. “The Diary of Elizabeth Simcoe,” published by William Briggs in 1911, is present in the gallery and is open to the quote above.

Also included in Elizabeth’s diaries are sketches of her whereabouts. She often made maps, drawings and paintings of the people and places around her. One such watercolour, Unidentified Landscape(179?), is displayed in the gallery. It depicts a rough rock face lined with trees that seem to be receding into waters. This could be a painting of her beloved Scarborough Bluffs!

In 1982, the same year that Doris McCarthy painted Hoodoo’s at Dinosaur Park, the artist Ana Mendieta had physically carved two abstracted silhouettes of the female body into the rock face at the Scarborough Bluffs. In preparation for these pieces, which were exhibited at the exhibition Contemporary Outdoor Sculpture at The Guild, in Scarborough On., Ana made a drawing on the back of a map of Guild park for the curator, Sorel Etrog. This drawing doubles as a map to the site where she made the reliefs. The book “Unseen Mendieta” by Olga Viso (2002) is present in the gallery, and is open to a spread that depicts the installation at the Scarborough Bluffs.

Ana made what she called Earth-Body works. She would often travel from the USA to Mexico or beyond to embed her body or the female form into the landscape. Ana would, for instance, cover her lying body with stones or use gunpowder to outline her body and light it from a distance. She would document these works in a series of photographic close-ups, the piles and residue left for the passerby to find by chance. These were neither grand earthworks nor isolated performances, but a distinct combination of the two.

While the book and map document the existence of her Earth-Body works, they were subject to the forces of forces of nature and, in their physicality, resist against historicization. With Ana Mendieta’s untimely death, the apparent disorganisation of the Guild exhibition, and the vast erosion of the bluffs themselves, the artworks became myth. It was not known until recently whether the reliefs were, in fact, more than a rumour.

Artist Alize Zorlutuna took up the quest to find out in The Presence of Absence: Searching for Mendieta (2014) and the sound work For Ana, For Earth (2014). Her compilation of works present in the gallery document Zorlutuna’s research around and attempt to locate the carved reliefs. By following the trail of the rumour, the artist sleuthed her way through archives and landscapes to find the mythical artwork. This (re)search is displayed in three parts: through a map, a soundscape and a collection of archive material and documentation.

The map, hand-drawn on the gallery wall using clay and sumac, details Alize’s trek. As a Turkish-Canadian settler, sumac holds particular relevance for the artist because one strain of the plant is native to North America while another hails from Turkey. Sumac, then, creates a transnational link that carries within it the stories of this land and Alize’s heritage. Accompanying the wall drawing is a display of archival research and a soundscape that gently fills the gallery foyer. The soundscape transports us to the Scarborough Bluffs, where the artist is searching for Mendieta’s reliefs. We are both here in the gallery and there on the bluffs, listening to one artist’s work while hearing about another’s. It is in this soundscape that we become privy to the connections between Zorlutuna and Mendieta’s practices. While contemplating the question herself, Zorlutuna asks us, “What is your relationship to this land?”By doing so, Zorlutuna resists the colonial notion that one’s relationship to the land they inhabit is simply one of ownership, and prompts a more in-depth consideration of one’s personal relation to the Scarborough landscape and also their historical connection to Canada as a whole.

Mendieta would physically and symbolically embed herself into various, significant landscapes drawing a connection between her body and the location. Zorlutuna, like Mendieta, carves an ancient symbol onto the surface of the Scarborough Bluffs. Where Mendieta replicated her own body and then the more generic, primal and graphic interpretation of the female form, Zorlutuna etches the Middle Eastern symbol of a Nazar. This symbol mimics the carving made by Mendieta in shape but not in meaning. Mendieta would physically and symbolically embed herself into various, significant landscapes drawing a connection between her body and the location. Zorlutuna, like Mendieta, carves an ancient symbol onto the surface of the Scarborough Bluffs. Where Mendieta replicated her body and a more generic, primal and graphic interpretation of the female form, Zorlutuna etches the Middle Eastern symbol of a Nazar. This symbol mimics the carving made by Mendieta in shape but not in meaning. The Nazar protects against the Evil Eye and by using a family heirloom, the ring handed down to her by her grandmother, to carve the shape into the rock, Zorlutuna casts an ancient and protective spell upon the bluffs.

The bluffs provide us with a model for multigenerational storytelling. They are visible records of geologic change and hold the stories of a particular place within their stratigraphic stripes. Each stripe is a record of a distinct period. Bluffs, constant in their erosion, are continually releasing the past and, in a way, resist it. They often line bodies of water and are subject to rapid and inconsistent decay.

As the edges erode to become steeper, the Scarborough Bluffs, which are present in the artworks of Ana Mendieta, Doris McCarthy, Elizabeth Simcoe and Alize Zortlutna, both mark time and recede from it. As the grains and detritus of the rock wall leave its surface, they recalibrate amongst the waves of Lake Ontario, coming together to make a new landmass: Toronto Island. These bits of old come together to create something new. Likewise, stories can relay the past in ways that inform and impact the present.

Treaties is the second photograph in a series of three digital photographs from Shelley Niro’s Border Series (2008). It depicts outstretched arms that clasp together. The hand gesture reflects the possibility of solidarity while the outstretched arms, though reaching to hold one another, create a borderline. Above the holding hands, a wampum belt grounds the image. Wampum belts are a method of recording used by the Haudenosaunee to narrate history, traditions and laws. Treaty offers us a story of old, perhaps one of Canada’s first colonial narratives, but also shows us something new. It presents the border as an imaginary line, one that can be tangibly delineated by the bodies it claims to hold. But Treaty also offers us possibility— one can view the border as an impassible boundary or as a place to reach across in solidarity and make a connection.

Andrea Chung’s video Untitled (Agatha Tears ) from 2009 is an excavation into a fictional lineage. With each diminishing image, another part of the Caribbean story is revealed and then sealed again. First, a picture of a woman sitting topless on a beach is immediately ripped away to reveal what appears to be a woman from a brightly coloured magazine spread. This spread, too, is peeled away to reveal a black and white photo of a woman from several decades past, then another family is exposed; finally, a portrait of another woman stares briefly at the viewer.

The video then reverses. The rips and tears mend, and we see the woman on the beach again. She is a tourist sitting on Caribbean shores. As her tranquil image is torn away by ghost-like, invisible hands so too is the simplified view of paradise. The tears make visible the hidden generations of women labourers. Through the continuous ripping and mending, Untitled (Agatha Tears) makes visible the struggle to maintain awareness of buried histories. This work, along with the reproduction of the cave drawings and the miniature of Nicholas Poussin 1638- 39 painting, Arcadian Shepherds, ground the exhibition as a re-working of art history.

In a curatorial gesture, a miniturized version of Poussin’s famed painting Arcadian Shepherds has been placed on the floor, leaning against a full-sized reproduction of cave art from La Cueva de El Castillo. Both images, the cave and the painting, depict what was at one time thought to be the very beginning of art history. In Poussin’s picture are four symmetrically placed figures- three shepherd men and an onlooking angel woman. The shepherds are kneeling at a tombstone, and one is pointing to the shadow made by the hand of another shepherd as he scrutinizes the stone’s inscription. The shadow, in effect, paints the hand onto the rock. This is thought to be an interpretation of the origins of art and the very first painting.

The cave, La Cueva de El Castillo, Spain, is where 40 800-year-old crowds of dots, geometric formations resembling public spaces and maps, animal silhouettes and hands stencils similar to the shadowed hand painted on the (tomb)stone of Poussin’s painting mark the walls. The hand stencils present in this cave, like others in the geographic region, are relatively small. Archaeologist Dean Snow of Pennsylvania State University and a team have analysed the images of, and negative spaces left by, hands in caves throughout the Cantabrian region of France and Spain. Snow and his team took measurements of each digit on the hand stencils (the negative space of a hand surrounded by pigment). When the size ratios were compared to a database of measurements from large populations of living people they found that 75 percent of the hand stencils were female, 15 percent were most likely adolescent, and only 10 percent were found to be those of adult males.

All of the past speculations attribute the hands to adult men, adolescent boys, male pygmies, or shamans but never once to women or children. This radical finding suggests that women and children were active cultural participants and that the scholarship on prehistoric art also functions under speculative patriarchal norms and that historically relevant conclusions have been made solely on cultural bias and without evidence. These are the norms that Poussin shows us in Arcadian Shepards, in which men are at the centre of artistic creation as women (an angel in this case) stands by in awe of His ability. The pigments are now fade but the strokes and forms are still visible today. The hand stencils indicate that whatever their purpose, females had an active role in mark making and were the most active of mark makers. Stories, then, are not merely versions of events that have happened in the ‘real world’, but are the “means by which events are interpreted, made tellable, or even liveable.” [3] To say that there are many stories here is to acknowledge the multiplicity of life experiences surrounding and included in this place and their specificity.

As a place where even children had access to participate in public mark making, I imagine that this cave is founded on a principle of mutual respect, difference that is accounted for, and on a multiplicity of connections. It is here that it is possible to build new and fluid narratives that do not privilege or reproduce the patriarchal man or univocal patriarchal values. What we have instead is many. Each hand, in its stencilling, leaves not a trace of its maker but affirms their absence. It is the anti-signatory mark, the mark that is individual but also collective amongst others. The hand stencil, then, marks the maker but also makes space for many more in its absence. In this way, it alerts the contemporary viewer to the many more stories (t)here.

[1] Roger Roulette interviewed by Maureen Matthews, CBC Ideas Transcript, “Mother Earth,” Toronto, ON, June 5, 2003, 6. As quoted by Leanne (Betasamosake) Simpson in Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back, (ARP Books: Winnepeg 2015), 71.

[2] Leanne Simpson, 73.

[3] Brownwyn Davies, ‘The Concept of Agency: a feminist poststructuralist Analysis” The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice no. 30 (1991) 42 – 55.

This exhibition is child-friendly. Children’s books in the Book Nook provided by Groundwood Books.

Chance the trek and download Alize Zorlutuna’s MAP (PDF, 17 MB) and SOUND WALK (MP3, 37 MB) to accompany you on your own search for Ana Mendieta’s El Laberinto de Venus in the Scarborough bluffs.

Programming

Monday April 24, 2017

Join us for story time in the cave and in the book nook! We will be reading Alego Written and illustrated by Ningeokuluk Teevee as well as Migrant Written by Maxine Trottier and illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault.

Books donated by Groundwood Books.

Sunday April 30, 2017

Free Contemporary Art Bus Tour

1– 4 pm

About the Artists

Andrea Chung is a Caribbean-American artist who is based in San Diego, California. Her multi-media practice addresses the colonial impacts of tourism on local cultures and they way tourists may conceive of locals as outside of their fantastic reality in paradisal spaces. Central to her practice are the histories of migration and labour in the Caribbean and the United States of America. In 2008, she received a Masters of Fine Art from the Maryland Institute College of Art. Andrea has exhibited her work extensively in the USA including at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego,CA (2017), New Image Gallery, Los Angeles, CA (2016), an Diego Art Institute, San Diego, CA (2016), and overseas. This will be the first exhibition of her work in Canada.

Shelley Niro is a member of the Turtle Clan, Bay of Quinte Mohawk from the Six Nations Reserve. Working in photography, painting, sculpture and film, Niro frequently utilizes parody and appropriation in her works to challenge stereotypical images of Aboriginal peoples, and women in particular. Often humorous and playful, her works address the challenges faced in contemporary Indigenous North American society. A graduate of the Ontario College of Art, Niro received her Master of Fine Art from the University of Western Ontario. Niro’s work has been broadly exhibited in galleries across Canada and can be found in the collections of the Canada Council Art Bank, Canadian Museum of Civilization, and Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography. Her award-winning films, including “Honey Moccasin” have been screened in festivals worldwide. Most recently, her video “The Shirt” was presented at the 2003 Venice Biennale. Shelley Niro lives in Brantford, Ontario.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson is a renowned Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar, writer and. Her work breaks open the intersections between politics, story and song—bringing audiences into a rich and layered world of sound, light, and sovereign creativity. Working for over a decade an independent scholar using Nishnaabeg intellectual practices, Leanne has lectured and taught extensively at universities across Canada and has twenty years experience with Indigenous land based education. She holds a PhD from the University of Manitoba, is currently faculty at the Dechinta Centre for Research & Learning in Denendeh (NWT) and a Distinguished Visiting Scholar in the Faculty of Arts at Ryerson University. Leanne’s books are regularly used in courses across Canada and the United States including Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back. As a writer, Leanne was named the inaugural RBC Charles Taylor Emerging writer by Thomas King. She has published extensive fiction and poetry in both book and magazine form. Her second book of short stories and poetry, This Accident of Being Lost is a follow up to the acclaimed Islands of Decolonial Love and will be published by the House of Anansi Press in Spring 2017. Leanne is also a musician combining poetry, storytelling, song writing and performance in collaboration with musicians to create unique spoken songs and soundscapes. Leanne’s second record f(l)light produced by Jonas Bonnetta (Evening Hymns), was released in the fall of 2016 on RPM Records. Leanne is Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg and a member of Alderville First Nation.

Alize Zorlutuna is an interdisciplinary artist who works with installation, video, performance, and material culture, to investigate themes concerning identity, queer sexuality, settler colonial relationships to land, culture and history, as well as labour, intimacy, and technology. Her work aims to activate interstices where seemingly incommensurate elements intersect. Drawing on archival as well as practice-based research, the body and its sensorial capacities are central to her work. Alize has her MFA from Simon Fraser University and is currently an educator at OCAD U, in Toronto.

Leave a comment